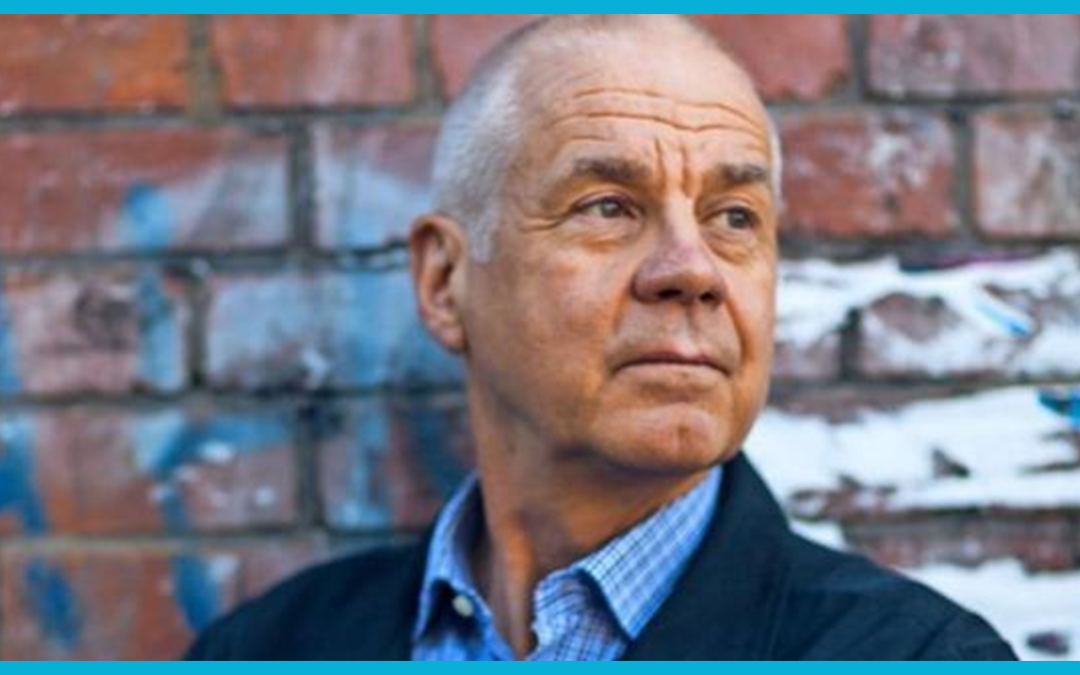

Is it possible to translate a funny German poem into English? Is it possible to express grief and loneliness with the same degree of subtlety in several languages? Does it help to talk to the author when translating a poem? These were some of the questions addressed by participants of a series of workshops and events on translating contemporary German poetry into English, focusing on the work of Matthias Politycki. Firmly established as one of Germany’s leading literary voices, Politycki has published a wide range of fiction and non-fiction books on issues as diverse as luxury cruise ships, marathon running, and a potential Third World War. In his heart of hearts, Politycki considers himself a poet, and it was the side of his oeuvre that undergraduate students at the University of Bristol along with Professor of German, Robert Vilain, and myself have explored for the past several weeks.

One of the most unusual facets of Politycki’s poetry is that he is able to write sonnets which both continue the august tradition of this classical form and inject a healthy dose of humour, melancholy, and critical awareness into it, thus achieving a blend of contemporary idiom, genuine beauty and prosodic precision that is quite unique in contemporary German poetry.

Translating contemporary sonnets

Robert Vilain’s translations are of a number of these sonnets. Robert Vilain has just published his translation of Rilke’s Malte with OUP and is also a distinguished scholar of the sonnet on which he has been teaching a course at the University of Bristol for several years.

“It was only in translating sonnets that I came to understand certain syntactical restrictions imposed by the English language on what can and cannot be said. Transitive English verbs need an object, and the object always follows the verb. Matthias’s poems often use verbs as rhyme words, and these verbs find themselves at the end of a sentence or clause, which is quite natural in German. If you want to use the verb as a rhyme in translation, you change the feel of the poem because you need to replace the neat end stop with an enjambement.” That said, Robert Vilain did not shy away from any challenge and even managed to produce an idiomatic and eloquent translation of poem with seven rhyme words using the same sound.

Metrically aware poetry

While the sonnets were taken from various different volumes, most of the poems chosen by Bristol undergraduate students for translation all came from Ägyptische Plagen, a slender collection of thirteen texts published with illustrations in 2015. Twelve of the thirteen poems are what I call “metrically aware,” and issues around rhythm took centre stage during both workshops and in the presentation of finished translations at an event in Bristol last night. James Hoctor pointed out that the anger of someone harrassed by a swarm of flies is best conveyed when he says that he wants to “squash it flat” rather than just “squash it,” echoing the strong emphasis on the final word of the original German line: “verscheuch’.” Chris Lloyd commented on finding lexical equivalents for neologisms, “zerflirren” and “zerflimmern,” with the prize going to the alliterative “flicker and fade away forever.” Ali Byam was faced with the difficult challenge of finding an equivalent for the innocuous word “gehen” in a mantra-like poem on a desert trek. Going or walking? Moving on?

Jeremy Williams noted that even contractions like “hinterm Felsen” (rather than “hinter dem”) create a casual tone which he captured in a similar contraction in the same line: “I’d barely settled down behind the rock …” Esther Kerrs-Farmer chose the only overtly metrical poem in the collection, “Ägyptische Plage (II)” and pulled off a stunt especially on the rhyme front. Onjuli Datta impressed her audience with this translation of two quite apodictic closing lines of “Damals das Glück”: “To not be thinking about you; back then, that was happiness.”

Amanda Merbis-Kirk tackled “Mittel gegen Zerknirschtheit” with its list of “favourite things.” Briefbeschwerer, Brillenetui, and kleiner Bernstein mit Blasen darin turn out to be “a paperweight, / a pencil case, / a small piece of amber, bubbles inside,“ thus preserving both the alliteration and the rhythm of the original text.

Translating contemporary German poetry — into your second language

My own attempts at translating “Diese schwüle Nachmittag damals,” the opening cycle of Dieses irre Geglitzer in deinem Blick, were marred by the fact that, for the first time, I was translating poems into my second language. It really brought home to me the difference between being a moderately competent speaker of another language and the kind of intuitive understanding of what is right and wrong, but as possible are impossible that you have developed in your mother tongue. I did enjoy working on the seemingly colloquial poems that nevertheless include numerous biblical references and somewhat antiquated individual words or phrases, resulting in the kind of uneven register that a non-native speaker almost inevitably produces.

Maybe my favourite poem to translate was “Hohelied” (Song of Songs). Spoken by an angry motorist stuck in traffic who watches a rather absurd woman crossing another road like as though it were the Red Sea, the poem posted the dual challenge of featuring a number of Hamburg street names (which can be localised to suit different cities’ traffic patterns) and relying in part on the divine status accorded to red traffic lights in German traffic.

A particularly witty translation was provided by Timothy J. Senior: Politycki’s “Nacht ohne Gnade” (Night without Mercy) is a sonnet in pictograms, mainly showing beer, wine, and cocktail glasses. There are two versions of the poem, one trailing off into sillier images of a rubber duck and a high-heel shoe, suggesting that the eponymous night may have ended with a thrilling meeting rather than a lonely hangover. Tim produced a version that was at one English (ale glasses instead of Bavarian wheat beer glasses), Bristolian (with the Clifton Suspension Bridge starring prominently), and contemporary — based on research into fashion changes in beer glasses, Tim was able to select the most up-to-date forms for his visual rendering.

Matthias Politycki generously shared his thoughts on many of his own poems at two events in Oxford and Bristol which, for all of us translators, served as a powerful encouragement to continue our work of translating contemporary German poetry into English. Our sincere thanks go to Margit Dirscherl for organising this entire project!